A great silence settles over the packed synagogue as a man cloaked in a white robe with a huge black and white striped Tallit over his head slowly raises and old Shofar to his lips. With majestic fanfare the Rabbi calls out in a rising and falling melodic tone, “Tekiah.” After a momentary, breathless hesitation, a piercing, reverberating blast trumpets through the silent sanctuary… One of my most prominent childhood memories is the sounding of the Shofar during the Rosh Hashanah service. Even today, the blast of the Ram’s horn sends a special kind of electric pulse through my spine. In fact, there are few of us who are not moved by the haunting call of the Shofar.

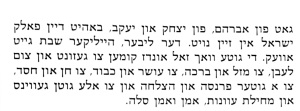

Sounding the Shofar, an ancient instrument made from the horn of a ram or similar animal is a tradition that dates back to biblical times. Most traditions trace the source of the Shofar to the story of the binding of Isaac, which we read on the second day of Rosh Hashanah. Abraham’s faith in God was so rigorous that he was willing to sacrifice his favorite son Isaac. At the last moment, an angel thwarted Abraham’s attempt to kill his son and a ram, caught in thicket of thorns was sacrificed in Isaac’s place. Thus the shofar reminds us not only of the solid faith and devotion of our ancestor but also of our connection through Abraham to God. We are also mindful that God preferred the sacrifice of the ram as opposed to what might have been an overly zealous, heinous act of child sacrifice.

A.Z. Idelsohn, perhaps the most renowned of all Jewish musicologists, points out that to the primeval Israelites, the Shofar was valued for its rhythmic rather than melodic capabilities. To our ancient ancestors, Idelsohn notes, the blowing of the ram’s horn had magical powers; with a blast of the Shofar, God could be awakened from His slumber and summoned to help His People. Furthermore, the Shofar could be used to frighten off evil spirts and lesser deities of neighboring peoples. Even God, remarks Idelsohn, was depicted as blowing His Holy Shofar in order to “frighten His enemies and to gather the remnants of His people…”

Our Machzor (High Holiday prayer book) cites as the biblical commandment to blow the Shofar a passage from Psalm 81, “Tiku Ba Hodesh Shofar… Sound the Shofar on our feast day, on the new moon when it is hidden. For it is Israel’s law, a decree of the God of Jacob.” According to Biblical and Rabbinic tradition, the Shofar was not only used on Rosh Hashanah but also on the first day of the new month, for the coronation of a new king as well as to proclaim the Jubilee year during which all slaves were freed and all land reverted to the clan that was its original owner. Similarly, a great celestial shofar sound was heard at the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai. Shofar blasts were also employed to call the Nation of Israel together for battle. Perhaps the best know example of the latter was the story of Joshua (Josh 6) whose famous resounding shofar blast brought down the walls of Jericho. In times when the Great Jerusalem Temple stood, the Shofar was often used in conjunction with a metal Trumpet and other instruments that served to punctuate the ancient sacrificial service.

Here is an audio recording of Tiku Ba Hodesh Shofar presented by Hazzan Moshe Schwimmer and his magnificent choir through the Judaica Sound Archives of Florida Atlantic University.

Shofarot(pl) are constructed using the horn of a Kosher animal. In recollection of the sin of the golden calf, horns made of cows are prohibited. While Ashkenazim (German and eastern European Jews) prefer shorter Ram’s Horns, Jews of other cultures use longer horns such as those from an Ibex or Antelope. Barsheset- Riback, an Israeli purveyor of Shofarot, describes the process of selecting, boiling, cleaning out and finishing the horns to produce a functioning Shofar. According to Jewish law, nothing, such as an external mouth piece may be added to the horn, neither can holes be drilled to produce variable sounds.

A day of Blowing [the Shofar] is one of the ways in which the Torah refers to Rosh Hashanah. As we usher in the New Year, the shofar is literally a wakeup call to our Jewish Soul. In fact, it is customary to begin the daily sounding of the shofar at the beginning of the month of Elul, the last month on the Hebrew Calendar, to awaken the listener to the need for undergoing the process of Heshbon Ha Nefesh, the accounting of the soul.

We are jolted into the reality of the High Holiday season – the need for self-examination and introspection in order that we can enter the New Year with a clean slate and a renewed spirit.

During our Rosh Hashanah liturgy the shofar is sounded in the context of the Shofar service that comes just after the Torah reading as well as to punctuate the three unique sections of the Musaph (additional service.) Please see my post on Rosh Hashanah Musaph for more details.

There are three distinct calls that are made on the shofar; each has its own significance and meaning. Noted authority on Jewish Liturgy Abraham Milgram traces the source of these distinct shofar blasts to the biblical book of Numbers (10:5-7) which defines a “Tekiah” – a solid sound and a “Teruah” – a wavering or broken sound. Because the Rabbis of the Talmud (R.H 34a) could not agree on what constitutes a “broken tone,” they mandated the “Shevrim,” a sound comprised of three medium length notes and the “Teruah” a blast consisting of nine short individual blasts. A “Tekiah Gedolah” or longer Tekiah is also used. The skill of the Ba’al Tekiah (Master Blaster) or one who blows the shofar, determines the quality and duration of each type of sound.

Here is a video of the four types of Shofar sounds:

Deep meaning can be found in each of the types of shofar blasts. The website Mazornet, a traditional site that focuses on resources and explanations for Jewish celebrations, posts an interesting understanding of the shofar blasts: Tekiah, is a regal sound appropriate for Rosh Hashanah which celebrates God’s coronation as Ruler of the Universe. Shevarim is compared to the sound of sobbing; the heart cries out for strengthening the relationship between God and the worshiper. Teruah is an alarm, the challenge to wake up to the call for Teshuvah, or return to a path that leads to a meaningful and fulfilling way of life.

This explanatory reading by Rabbi Milton Steinberg, the great Conservative theologian appears in Machzor Hadash, published by the Prayer Book Press:

For untold generations, on this day, our ancestors listened to the sound of the Shofar. What did they hear in its piercing tones? What solemn truths did they detect in its calls which stirred them so profoundly each year?

And what does the Shofar say to us today, as we stand at the dawn of the New Year, groping for a light to guide us and a faith to sustain us?

Tekiah! Awake! Let not habit dull your minds, nor comfort harden your hearts. Examine your deeds, look well into your soul, mend your ways, turn to God.

As we hear the sharp Tekiah blast, let us rouse ourselves from smugness and self-satisfaction, from callousness and self-righteousness.

Shevarim! The broken refrain! Listen to the staccato cry. Hear the echoes of sighing and weeping. The deprived and the distressed, the neglected and the enslaved, the bruised and the broken-all cry out for relief from their pain, for release from their torment.

As we hear the anguished wail of Shevarim, let us open our ears to the cries of the afflicted and the oppressed, and let our hearts respond with compassion and love.

Teruah! The call to battle is sounded: Join the struggle against evil and suffering. Give of your bread to those who hunger; give of your strength to those who stumble; give of your time to the lonely and forsaken; heal the wounded, comfort the bereaved.

Let us hearken to the Teruah’s call to action.

For in our hands, in our hearts, and in our minds

Are the means for building a better world,

For fulfilling the promise of peace and justice,

And for hastening the day when all will hear

The sound the great Shofar of liberation.

Hopefully, the blast of the Ram’s horn will send a special kind of electric pulse through your spine and reverberate in your soul this Rosh Hashanah so that you too will moved by the haunting call of the Shofar. May you be inspired by the sounds of the Shofar to strive for a Shanna Tova, a year of Blessing and Goodness.

I hope you enjoy this brief look at part of our prayer service. If you have a suggestion, comment or question, please fee free to leave a comment below or to email me at michaelkrausman@gmail.com.

Take Care

Hazzan Michael Krausman